Designing for the Vulnerability of the Other: What Love Looks Like in Urban Design

In an essay for The Guardian newspaper after the unfortunate celebrity photo leak of 2014, author Roxane Gay detailed why this sad and criminal act only reinforced an ongoing vulnerability women and other marginalized populations continue to experience in our society. She writes: “…privacy is a privilege. It is rarely enjoyed by women or transgender men and women, queer people or people of color. When you are an Other, you are always in danger of having your body or some other intimate part of yourself exposed in one way or another. A stranger reaches out and touches a pregnant woman’s belly. A man walking down the street offers an opinion on a woman’s appearance or implores her to smile. A group of teenagers driving by as a person of color walks on a sidewalk shout racial slurs, interrupting their quiet.” She continues: “For most people, privacy is little more than an illusion, one we create so we can feel less vulnerable as we move through the world, so we can believe some parts of ourselves are sacred and free from uninvited scrutiny.” She explains that what the hackers did only serves as a reminder to these women that “no matter who they are, they are still women. The are forever vulnerable”.

In a brief and passionate speech (above), actress and activist Laverne Cox discusses her experience being a transgender woman of color and illustrates how intersecting issues of transphobia, racism and misogyny can play out in public spaces. When Ms. Cox shares a past experience with street harassment, she attempts to highlight the precarious position in which she, and other trans women of color can sometimes find themselves. Ms. Cox ends the speech by suggesting that love may be a solution to putting an end to these types of incidences and quotes Cornell West who says “justice is what love looks like in public”.

In recent years, we seem to be hearing an increasing number of stories about violence perpetuated against transgender and gender non-conforming individuals as well as heart-wrenching accounts of young people who feel alone and hopeless and end up taking their own lives. These awful stories from our LGBTQQ community only add to a catalog of other similar stories of public harassment, violence and discrimination against racial and religious minorities. As someone who spends a lot of time thinking about how to create safer public spaces (our streets, parks, plazas and other gathering places), I wonder how these experiences can inform better urban planning, policy and design and how that design might contribute to the safety of our most vulnerable populations.

Existing design guidelines only take us so far. For example, public space design guidelines attempt to promote design strategies that create spaces inclusive of a wide variety of users and modes of transportation, but often fail to address social issues like gentrification. Other guidelines attempt to improve environments for specific reasons (like creating permeable surfaces for water retention or constructing a protected bike lane); or specific populations, often those with physical challenges (like the deaf community who orient themselves through vision and touch or seniors who may have fluctuating levels of mobility). These kinds of recommendations are an exciting addition to the world of urban design but they don’t necessarily address more comprehensive safety issues.

First, I want to take the opportunity to acknowledge my own limitations in discussing this work. I am a white, straight, able-bodied, cis woman, and I recognize that these attributes shape my outlook on the world. Additionally, I understand that my personal experiences, specifically my level of comfort in a public space, are not universal experiences. These statements may seem obvious but it may be less obvious how these attributes influence my professional work and the lens in which I view policy, planning and design initiatives for the general public. Am I humble enough to listen or try to empathize with the stories of our most vulnerable populations? How often do I think about the struggles of those who have dissimilar experiences to my own and how do I begin to create respectful dialogue with the hope of informing better urban design?

Community engagement is an integral part of a successful design process. Engagement can be achieved through strategic outreach like holding public meetings, reaching out to community leaders and taking time to listen to, and collect knowledge from the existing community. But I would also like to suggest that while less effective, design may also be informed through first-hand stories, like the essay and speech above, which are not traditional stories about design. After beginning the community engagement process, conducting research, and thinking more critically and contextually about these issues, how do we then use that information to create more relevant design? It may be helpful to begin by looking at larger issues around safety.

As I’ve previously discussed on this blog, my masters thesis investigated deterrents to bicycling for women in New York City. As this project evolved, my questions revolved much less around cycling and more about women’s relationship to safety in the built environment. While interviewing women and reading literature about perceptions of safety, what became very apparent to me is that there is no such thing as “irrational” fears. For example, a handful of women I spoke with told me that they were afraid to ride a bike because they thought someone in a van could pull up next to them and grab them. While this occurrence may not actually be a frequent event, these women’s fears shouldn’t be invalidated because when we understand the context for these fears, we recognize that they represent a larger issue about perceptions of safety that have been informed by personal experience. Instead of dismissing these concerns, we could ask ourselves what elements of urban design could contribute to someone feeling less likely that something like this would happen?

In the survey I conducted, the number one deterrent to bicycling for women was riding a bike a night. Some existing literature suggests that women are less likely to ride bikes because they are naturally more risk averse, but I would argue that it’s more likely that negative past experiences and particular circumstances (like traveling with children) make some women less willing to be alone in environments where they are uncertain of their surroundings. So how can we create a safer experience for these women if they choose to ride a bike at night at some point in the future? Well, we know that lighting, visibility and location are some of the factors that can contribute to safer streets and public spaces, so using our previous example, it would not be necessary to design bicycle lane infrastructure that specifically prevents vans from pulling up and grabbing a cyclist off the street, but if we installed a bike lane on a well-lit street with a lot of visibility and foot traffic, we could create a safer environment for riding a bike and in doing so, limit a myriad of other potential safety concerns.

It may seem like an endless task to try to identify and document an unknowable number of negative experiences and fears a person may have in our public spaces but I don’t think that’s the point. What if instead, we try to think of one person who is the embodiment of the vulnerability of the Other: someone who has some of the largest physical and social challenges in our society? Maybe by imagining that person in our public spaces, we can inadvertently address the needs and fears of a larger cross-section of users and in doing so, create some of the safest, most well used public spaces possible. What would that person look like? Who would they be?

For this purpose, I’d like to try and incorporate some of our earlier examples and suggest that we think of “Joy”, an elderly, black, deaf, transgender woman in a wheelchair. How could Joy more easily traverse a busy boulevard, enjoy a sunny day at the park alone or gather with friends in a public plaza? Through design, how can we make Joy feel safe, provide her with easy accessibility and create a space in which she feels comfortable enough to want to spend time there? What would these spaces look like?

Even if we don’t know someone like Joy, she represents some of the voices that should be at the table. Wondering how Joy may interact with public spaces allows practitioners to create environments that contribute to the safety of other underrepresented individuals. Ultimately, we can’t guarantee that our streets, parks, plazas and other public spaces will be able attract with widest spectrum of users, but by attempting to serve the needs of the Other, at least we can say that we tried. Designing public spaces in this way is what love looks like in design.

Just Smile

For the last five years I’ve been a transit-dependent person. What this means is that I spend a lot of time on foot, a lot of time standing waiting for buses, waiting for trains, and it may or may not surprise you to know that I experience at least one form of street harassment nearly ever day.

There is a spectrum of severity to these experiences but their regularity does not make them easier to endure and their consistency has resulted in a vulnerability that can sometimes feel overwhelming. I’ve never gone unaffected by someone who yells to try and get my attention, intentionally standing back to look at me up and down, walking up to me and putting their faces inches from my own, or honking their horn or making suggestive faces from their car.

I often try to brush these experiences off but I know they’ve affected me. When I’m getting dressed in the morning and purposefully choose to wear clothes that hide my body, when I avoid eye contact on the sidewalk, when I rush to get home before the sun goes down, when I choose not to participate in activities that require long trips, when I hold my breath as I see someone walking towards me at night. I know it affects me.

I experienced the worst form of street harassment in my previous neighborhood. Sometimes I would walk past groups of men seated on the sidewalk who would feel the need to comment on what I was wearing, talk about my body, or inform me that I’d be prettier if I just smiled. Sometimes these men would have the audacity to become outraged when I would ignore them and they would stand up and yell profanities at me as I walked away.

It can be difficult to talk about experiences of harassment but sharing experiences is an important step in raising awareness about the issue. Not only to let those who are being harassed know that they are not alone, but to educate the public about this important issue and reiterate publicly that this is not something that we should just accept as a society.

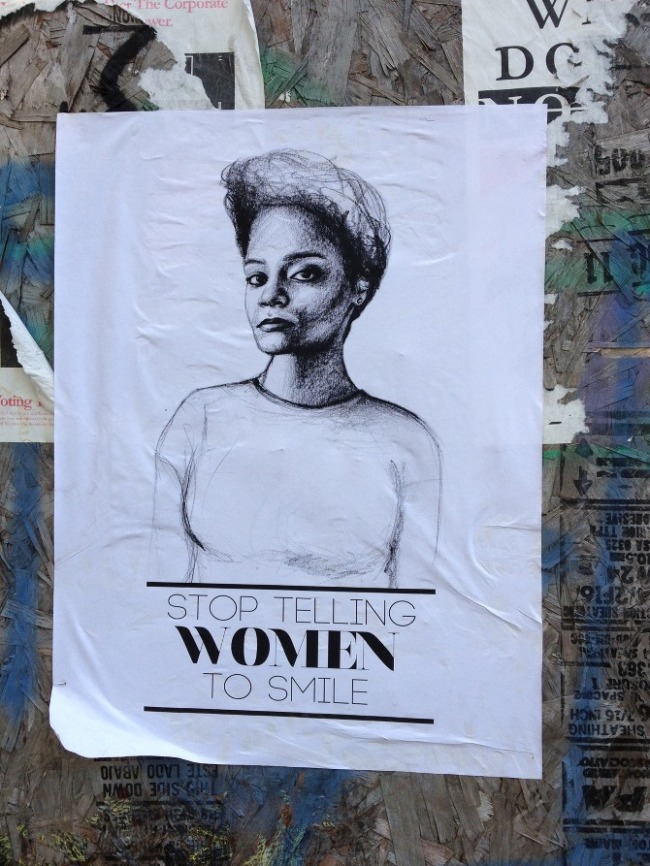

Artist Tatana Fazlalizadeh has attempted to raise awareness about this issue in a very creative and public way by creating posters that reflect women’s stories and struggles with harassment. Ms. Fazlalizadeh says that her work “attempts to address gender based street harassment by placing drawn portraits of women, composed with captions that speak directly to offenders, outside in public spaces.”

She goes on to say that “Street harassment is a serious issue that affects women world wide. This project attempts to take women’s voices, and faces, and put them in the street – creating a presence for women in an environment where women are a lot of times made to feel uncomfortable and unsafe.”

By bringing this work in to the public realm, Ms. Fazlalizadeh creates the opportunity to simultaneously speak to those being harassed, those doing the harassing and those who may not have the issue on their radar. She is empowering those who may feel victimized by giving them a voice and by allowing visitors on her site to obtain her posters for FREE!, she is strategically given those who want to raise awareness about this issue, the opportunity to do so in their neighborhood.

Yemen Women Create Safer Streets with Technology

Last May, I read about a woman from Yemen named Ghaidaa al Absi, whose organization Kefaiaa was training over 200 women to become cyber-activists and work with other cyber-activist to fight against street harassment in their country. Street harassment is a serious problem in Yemen and the country does not have any legislation protecting women from sexual harassment. While police had indicated they would step up efforts to stop harassment, those charged for harassment have received little to no punishment for their crimes.

A challenge many Yemen women face in becoming cyber-activists is access to mobile devices and inconsistent internet connection in their neighborhoods. Tactical Technology Collective, an online resource which provides open source toolkits and resources to cyber-activists gave Absi’s group a micro-grant to develop the Safe Streets website which allows women to report real-time incidences of street harassment. Absi’s organization continues to grow and expand and she recently launched an art exhibition which addressed the issue of street harassment in Yemen (check out the some of the artwork below).

For many countries across the world (and certainly for neighborhoods, and regions here in the US), lacking access to technology can be an incredible deterrent to connecting with online tools that help connect you to basic services and give you a voice. Companies like Tactical Technology Collective can help make an incredible difference in erasing these barriers and giving representation to those who most often need it the most.

The Skateboarding Girls of Kabul

Get ready. A skateboarding revolution is happening amongst young girls… in Afghanistan.

In 2009, Skateistan (an NGO and Afghanistan’s first skateboarding school) opened the doors to it’s 5428 square meter facility in Kabul, providing recreational sports and education and creative arts classes to boys and girls ages 5-17. According to Skateistan, 60% of Afghanistan’s population is under 25 and 50% is under the age of 17. Children without education (an especially girls – only 12% of Afghan women are literate) have few opportunities open to them. Skateistan aims to provide children with a safe place for education and recreation and hopes to instill each one of their students with confidence, team work and leadership skills, to help them become empowered individuals who affect change in their community.

Each week, Skateistan welcomes over 400 children, half of who are children streetworking children, some are refugees, some are disabled and 40% of all the children are girls. To help make the facility more accessible, Skateistan provides transportation to and from the facility (women and girls are usually not allowed to travel alone and getting around Kabul can be difficult with traffic congestion, limited public transportation and street harassment) as well as skateboards, other sports equipment, safety gear and educational materials.

Afghanistan’s Girl Skaters – Kabul 2012 from Skateistan on Vimeo.

Ovarian-Psycos Bicycle Brigade

While studying urban planning in graduate school I became fascinated with the sociology of public space. Why were some paces used more than others and why were some spaces perceived to be inclusive or exclusive by certain populations. During an internship in the New York City Department of Transportations innovative Office of Public Spaces, I began to understand that our streets were actually our largest public spaces and through public plazas for example, they had the ability to be transformed in to spaces that prioritized pedestrians instead of cars.

For my master’s thesis, I merged my interest in public space analysis, transportation planning and women’s studies by looking at what deters women to ride bicycles in New York City. Not unsurprisingly, motorist aggression and fear of personal safety were the greatest deterring factors for women but what surprised me were the limited opportunities encouraging those unfamiliar with riding a bicycle and the lack of attention to the needs of a wide variety of users in the design of our cycling infrastructure and facilities.

In spite of the ground that women have gained in the fight for equal rights, studies have show that women are more likely to run household errands and transport children and elderly family members. For some women, this can make their travel behavior and willingness to take risks different from that of a single rider traveling from Point A to Point B. Often, I look for examples of thoughtful cycling infrastructure and the encouragement of bicycling to a wide variety of users (specifically women) so today I was ecstatic to read about the Ovarian-Pyscos, an East Los Angeles bicycle collective, in Los Angeles Streetsblog.

The Ovarian-Psycos Bicycle Brigade, an all-women bicycle collective from East Los Angeles, is not only supporting one another in cycling through the city and raising awareness about cyclists, they have become a powerful collective supporting women’s rights, social justice and each other.

From Los Angeles Streetsblog:

“Two months ago, when 22-year-old Bree’Anna Guzman was murdered in Lincoln Heights, the all-women bike group Ovarian-Pscyos Bicycle Brigade scrapped their previously planned ride to ride instead through the neighborhood to protest the killing.

‘Whose Streets,’ one woman called out.

‘Our Streets’ the more than 30 women riding answered.”

“Many of the women say they feel they are not taken seriously in the biking community because their rides aren’t as long as traditional rides, there are usually many first-time riders, and the ride will stop and wait for one person. But, these limitations, Ova member Natalie Fraire said, can be a positive.

‘We are encouraging a lot more riders and that’s more important, said Fraire.”